“This star I am wearing is for my husband, a member of the great Sioux Nation, who is a volunteer in Uncle Sam’s Army.” From Gertrude Bonnin (Zitkala-Ša), writing in The American Indian Magazine, in an article on WWI

Veterans Day—a day to honor all the women and men who have served as members of the United States military—has just passed by. Parades, free meals for veterans at some generous restaurants, fly-overs and parachute-ins at football games: these are just a few of the ways I appreciated seeing the day being celebrated.

I write today, though, in the hope of extending its reach, with a special focus on Native American veterans. (Thanks, in that context, to my TCU colleague Scott Langston for highlighting, in an email yesterday, Native students at our university who are veterans.)

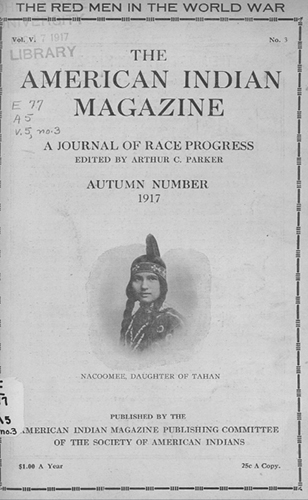

It’s well worth noting, in fact, that Veterans Day sits on the calendar in the middle of a month established by the US government, beginning in 1990, as Native American Heritage Month. The national designation built on foundational work by Native American proponents like Red Fox James and Dr. Arthur C. Parker (Seneca), though it did benefit in visibility from the imprimaturs of multiple US Presidents. In that vein, for instance, President George H.W. Bush’s August 1990 declaration was later echoed in several similar proclamations by Barak Obama during his presidency.

The choice of November as the month for Americans to focus on the historical and cultural leadership of Native peoples is, of course, ironic. November is also the time of year when, as the website for the compelling “Americans” exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) reminds us, we close out the month with a national holiday which has a complex, often painful resonance among Native peoples: Thanksgiving. Accordingly, Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche) explains, white Americans have long used the story of a “neighborly” shared meal in Plymouth to sustain an aspirational story about the meaning and values of our nation. Yet this story downplays, even sometimes erases, the suppression of Native peoples from historical memory.

If having this particular month be the one officially designated for honoring Native peoples might have its drawbacks, what should we say about our current President’s moves to counteract the practice, on several levels? Quoting Simon Moya-Smith (Ogala), Nathsha Lennard wrote last week for The Intercept that Trump’s move to re-envision the month as also officially celebrating “’The Founders’—white men who in the Declaration of Independence explicitly referred to Natives as ‘merciless Indian savages’”—dishonors Native American Heritage Month. Thus, Lennard argues: “The addition of a National American History and Founders Month—especially during the same timeframe—is cruel Indigenous erasure, pure and simple.”

And this is not the first time—or the only way—that our current President has chosen to disrespect the place of Native peoples in the American past, present, and future. As several other news outlets have noted since the start of November, it’s part of a pattern. My own December 2017 blog spotlighted one part of that pattern in by reporting on Trump’s moves against Bears Ears National Monument and his associated interactions the World War II Code Talkers in the Oval Office, strategically positioned in front of the portrait of President Andrew Jackson, architect of Indian Removals.

In that earlier blogpost, I pointed to the Code Talkers as a powerful example of the contributions Native veterans have made to the US military—in spite of the painful history of indigenous communities being victimized by that same military via Removals and warfare—often including assaults on women and children, as at Wounded Knee.

If we want to make November a truly appropriate time for honoring Native Americans, let’s shift our focus from Thanksgiving to and extended Veterans’ Day. Turning again to the National Museum of the American Indian, we can visit their thoughtful online materials for “Patriot Nations: Native Americans in Our Nation’s Armed Forces,” where the opening page presents a forceful reminder from Jeffrey Begay, a Diné [Navajo] veteran: “We serve this country because it’s our land. We have a sacred purpose to protect this place.”

Medal awarded by the Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 to the Tlingit tribe of southeast Alaska for its service in World War II. Designed by Susan Gamble, engraved by Renata Gordon and Joseph Menna, 2013. Gold. Diam. 3 in. United States Mint.

War bonnets adorn uniform jackets at a Ton-Kon-Gah (Kiowa Black Leggings Warrior Society) ceremonial near Anadarko, Oklahoma, 2006. Photo, NMAI.

Another opportunity to learn and reflect on the special contributions of Native Americans as veterans comes via the National Archives, which is presenting a timely documents exhibit honoring Native people who fought in World War I.

If, like me, you can’t make it to Washington, DC, exhibits in person this month, I invite you to read a few of the online artifacts from The American Indian Magazine’s engagement with the topic of World War I’s Indian service members and associated topics, now available to everyone through the generosity of the Hathi Trust.

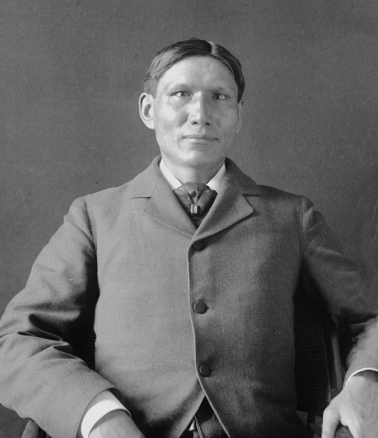

For instance, one war-time issue of the magazine printed a speech Arthur C. Parker had recently given in Albany, dubbing American Indians who were fighting for the Allies “world patriots” and situating their bravery in a long tradition of Indians fighting for just causes in America:

“There were Indians in the regiments of Washington, there were Indians in the first battles of the Revolutionary war, at Lexington and at Bunker Hill, in the campaigns in the Hudson Valley and about New York. In every battle of the nation since that time there have been Indian patriots willing to lay down their lives for the triumph of a nation conceived as this nation was conceived”—that is, for the most aspirational version of US nationhood. Noted Parker: “Though they have suffered much injustice, though every treaty forced upon the Indians has been broken by the [United States white] Nation, though their lands have been taken from them, their women and children massacred by our military units, though they have been repressed and segregated, yet in this world struggle, this gigantic war for human freedom, for the establishment of government of men by the consent and cooperation of the governed, the American Indian is loyal to the United States and to the cause of the Allies” (16).

“There were Indians in the regiments of Washington, there were Indians in the first battles of the Revolutionary war, at Lexington and at Bunker Hill, in the campaigns in the Hudson Valley and about New York. In every battle of the nation since that time there have been Indian patriots willing to lay down their lives for the triumph of a nation conceived as this nation was conceived”—that is, for the most aspirational version of US nationhood. Noted Parker: “Though they have suffered much injustice, though every treaty forced upon the Indians has been broken by the [United States white] Nation, though their lands have been taken from them, their women and children massacred by our military units, though they have been repressed and segregated, yet in this world struggle, this gigantic war for human freedom, for the establishment of government of men by the consent and cooperation of the governed, the American Indian is loyal to the United States and to the cause of the Allies” (16).

Along similar lines, in “America, Home of the Red Man,” author-editor Gertrude Bonnin imagined a conversation with a white traveler who, seeing her wearing the star that signified being the relative of a serviceman, was initially surprised to learn of the thousands of “Indian soldiers swaying to and fro on European battle-fields—finally mingling their precious blood with the blood of all other peoples of the earth, that democracy might live” (165). Recalling the story of on “Indian brave in the Army uniform,” she retraced his many roles in the War, from machine gunner to trainer of military horses, until, when no longer able to fight due to serious wounds, he took on “garden work” growing food “to help win the war” (166).

In “The Indian’s Plea for Freedom,” Eastman (Ohiyesa) wondered if the time of the Peace Treaty being hammered out in Paris might also bring, to Native Americans, full citizenship in the nation so many had selflessly fought for (165). Meanwhile, in her “Editorial Comment” for the same issue, Bonnin affirmed calls from “Labor organizations” and “Women of the world” to have their place in the American community fully recognized, but she also pointedly underscored the need for the “Red man,” so many of whom had “made the supreme sacrifice for liberty’s sake” in the just-concluding global war, to be rightly honored with “citizenship in the land that was once his own, ‒America” (162).

Let’s expand our calendar for Veterans Day throughout the month of November, and let’s embrace the opportunity to honor, in particular, the countless Native Americans who, despite past and continuing patterns of discrimination and oppression they have faced in a land taken from them, have been among the bravest and most dedicated of those serving in the US military.

Thanks for this.

Too often we think the native America contribution to the war efforts have been the Code Talkers.

LikeLiked by 1 person