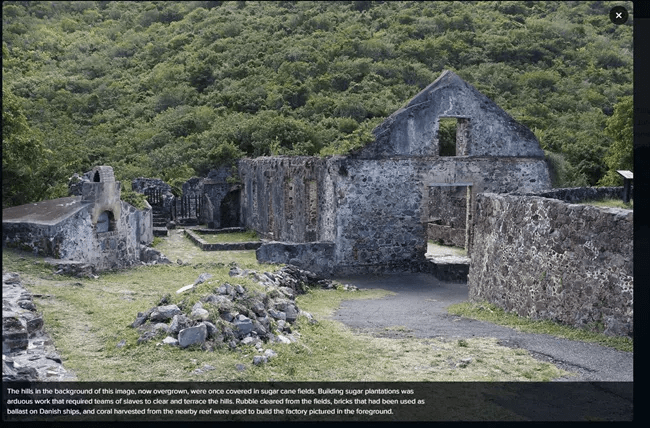

The breeze is gentle as I stand at a cluster of ruins on St. John, USVI, but the history here is not. Catherineberg is one of several sites on the island that mark where enslaved people labored long, hot, debilitating hours to produce sugar.

The Catherineberg site has not been re-cast for more formal, official storytelling like the National Park Service’s larger arrangement on St. John at Annaberg Plantation. a location more extensively “labeled” with informative signage. That more extensive set of ruins has even been rendered, in digital form, into a teaching resource to be explored without even coming to the island.

Catherineberg is a far more quiet, far smaller ruin. It’s not a site marketed (like Annaberg) by tourist organizations for a tour aimed at “learning about” Caribbean slavery’s still-present past. To reach Catherineberg requires time on back roads. It requires watching out for turns, steering around deep potholes, slipping back into the woods.

It is a lonely place.

But maybe that loneliness opens up a different kind of story-making energy? Maybe the haunting here is more palpable? Maybe it’s a place to go to hear what poet-scholar drea brown has compellingly dubbed “haints.”

Photos by the author

Even here, though, rock-ruins offer only a partial, muted testament today to enslaved suffering. Suffering and resilience.

A tree now grows where the punishing labor of sugar-making happened, hour upon hour. Ferns and weeds reach out, with seemingly quiet innocence, from cracks along walls and in crumbling stairways and along a ramp whose endpoint would have pulled those enslaved laborers into constrained dark space, where only a small strip of sky was visible, remains visible now as a reminder of that long-ago-still-with-us-all past.

Here Black suffering made that sweet white commodity much favored by whites back across the Atlantic. Carrying their born-from-cane cargo, the ships passing in that west-to-east transatlantic direction also bore, however suppressed then, yet partially recoverable today in counter-stories, Black ghosts. Ghosts of horrific Middle Passage journeys from Africa to the West. (See my discussion of the young child Phillis Wheatley’s Middle Passage experience in an earlier blogpost here. See a collaborative project honoring Wheatley (Peters) as teller of counter-stories here.)

Image credit: Library of Congress

Those tightly packed ships crossing Africa-to-Americas brought captured humans to inhuman life situations that, typically in Caribbean sugar-making, lasted only about 20 years, given the fully-expected high death rate in such mills.

Conditions in the Dutch colony of St. John were so brutal in the early eighteenth century that the island witnessed one of the most determined revolts by enslaved Blacks–the 1733 Akwamu insurrection. This revolt temporarily took control of almost the entire island, until reenforcements intervened, sent from other European Caribbean colonies fearing what sustained success might mean for their own brutal enterprises.

And yet, I cannot stop loving St. John today: for the beauty passing in roving shafts of ever-varirable light across its hills each day, for the beauty living in its waters.

So I struggle, whenever I return here, more than twenty times across decades, to reconcile somehow with history. I reflect, unsuccessfully each time, on how best to confront and acknowledge this history. As a white traveler, how should I engage with this beautiful island’s long dependence on slavery to build material wealth for the Dutch who ran the sugar mills? And the other Europeans who came to aid their fellow enslavers during that ultimately-unsuccessful revolt of 1773? And the generations of whites tapping into its natural resources since those long years of colonial times, never clearly post-colonial?

Even now, of course, legacies of these personal and systemic histories remain. Black-owned businesses are clearly fewer than white ones. On a positive side, I’ve been coming to St. John long enough to see some progress. The National Park Service’s phased reopening of Caneel Bay area (formerly an exclusive resort that, sadly, creating polluting impact on the island) is attending not only to goals of environmental justice but also to inclusivity in access and opportunity. Blacks are increasingly managers of stores and restaurants, not just servers. Increasingly, we connect with National Park employees who are longtime Black residents of this place or St. Thomas, just a short 15-minute daily ferry ride away. Having taken that same ferry for almost five decades, I can appreciate the change our rental house’s management company has made, shifting away from selecting white greeters (however long on the island) to shepherd us to our temporary homeplace. Now local Blacks whose families have lived here for generations welcome us when we diembark from Red Hook, and we can share stories of our own past visits, hear about their families, some now on the mainland, some still here. But other jobs held by Blacks in the tourist industry remain less genteel. The gardener who comes once during the week to tend to our rental’s lovely landscaping is also far more likely to be Black than white, as is the crew that cleans our rental when we leave, preparing it for the next guests, probably white like us. Overall, many, perhaps most, of the jobs open to locals involve serving white tourists in ways I can only hope are not too closely aligned with the hierarchies Jamaica Kincaid has so incisively critiqued in A Small Place, her bitter parody-like “tourist introduction” to her own Caribbean island home. When I teach this text, students are often troubled by its tone. Many resist its anger, despite my efforts to explain, to show yet another collection of personal photos I took on her “small place” island, several directly validating descriptions in her narrative.

Given this ongoing history across the Caribbean islands, is my time at at these St. John sugar mill ruins merely an unworthy, ineffectual intrusion into a history I will never be able to honor rightfully?

I think of Lucille Clifton’s moving poem where she describes seeking the names of individual enslaved people in burial grounds at another plantation. Her elegy-like lyric, “At the Cemetery, Walnut Grove Plantation, South Carolina, 1989,” opens as a personal call to that plantation’s rock ruins, in a graveyard that aims to ignore slave history.

among the rocks

at walnut grove

your silence drumming

in my bones,

tell me your names.

I can claim no right to speak in a comparable voice to Clifton’s. And I know that aiming for cultural humility, trying to enact empathy by listening for lost voices on-site, or to offer words like these afterwards, can never be adequate.

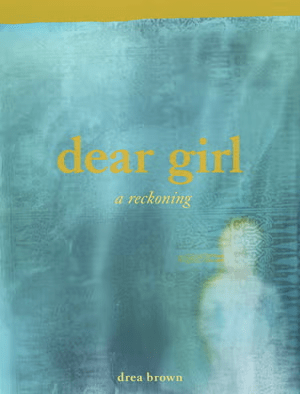

Noting the crystal-blue sky as I try again to again to frame a respectful photo at Catherineberg, I think of drea brown’s dear girl, a reckoning, with its ocean-tinted cover recalling Phillis Wheatley’s Middle Passage, with its ghost-like image there, too, conjuring what brown elsewhere compellingly terms a “haint.” I remember Toni Morrison’s envisioning of re-memory of Middle Passage ships in Beloved. I re-see Rebecca Hall’s imaginative archival work in her striking graphic narrative, Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. Like Clifton, these Black women writers are the righteous history-tellers. They invoke historically informed narrative imagination to fill in lost gaps, to invite their readers to become witnesses at a remove; that is, they skillfully employ what Saidiya Hartman calls “critical fabulation.” Standing in Catherineberg’s ruins, I again appreciate the insights in their words, the power of their imagery.

Hauntings like that embodied in brown’s ship-shaped lyric in dear girl should also call all white readers to shared shame as well as sorrow. I know I can never write in a comparable space of epistemic privilege. Where does my own epistemic responsibility find a path to speak? And to whom can I offer my hesitant story-telling?

No, let the ruins speak instead. Here, I hear. Here, if I draw on Saidiya Hartman’s call to embrace critical fabulation–to invoke imagination as a means to find memory-at-unbreachable-remove–can I at least assemble a tiny, modest archive to share with students who often know nothing of this history? Can I encourage them to cultivate, at the least, an awareness, a willingness to learn more?

For further reading:

brown, drea. “Conjuring the Ghost: A Call and Response to Haints.” Hypatia 36 (2021): 485-502.

brown, drea. Conjuring the Haint: The Haunting Poetics of Black Women. University Press of Mississippi, 2025.

brown, drea. Dear Girl: a Reckoning. Gold Line Press, 2015.

Clifton, Lucille. “At the Cemetery, Walnut Grove Plantation, South Carolina, 1989” In The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton. BOA Editions, 2012.

Clifton, Lucille. “At the Cemetery, Walnut Grove Plantation, South Carolina, 1989” In Lucille Clifton Papers, Emory University: https://archives.libraries.emory.edu/repositories/7/archival_objects/128457

The Genius of Phillis Wheatley Peters project website: https://wheatleypetersproject.weebly.com/

Hall, Rebecca. Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts. Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14.

Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1988.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. Alfred A. Knopf, 1987.