A Poignant Anniversary with Implications for Teaching

Phillis Wheatley arrived in Boston from her African homeland 260 years ago this month, in July 1761. Though only about seven or eight years old, she was transported with other captives aboard the Phillis as part of an ongoing push to make slavery central to the economies and politics in North America. What did this fragile, journey-weary little girl think upon being re-named for the ship that had brought her, after being purchased by a New England merchant, John Wheatley, and designated as a gift for his wife, Susanna?

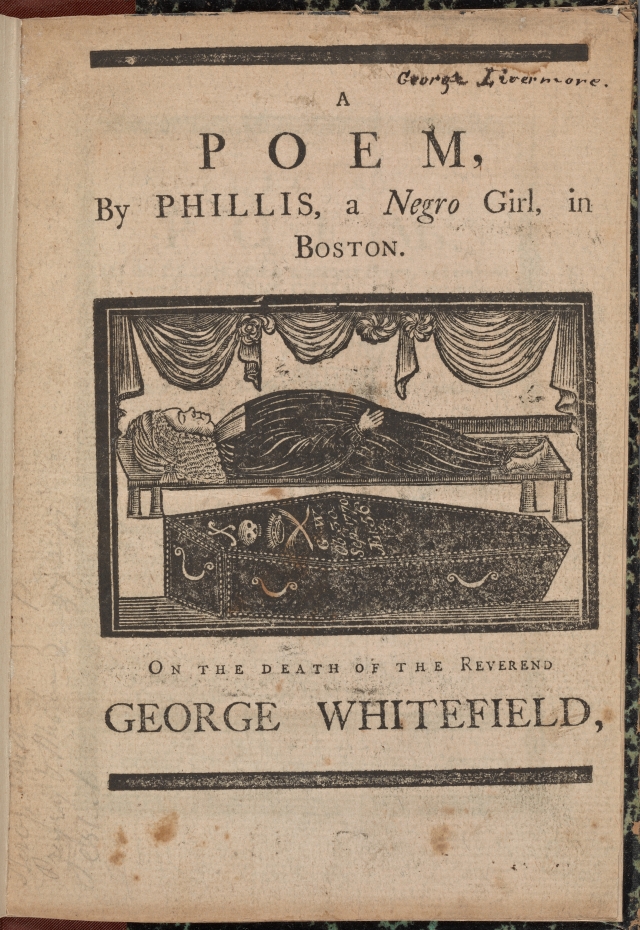

We can read accounts Wheatley wrote later about her feelings. Perhaps the most-often-reprinted is “On Bring Brought from Africa to America,” which Henry Louis Gates, Jr., memorably dubbed “the most reviled poem in African-American literature,” given its casting of enslavement as a “mercy” (‘Trials,” 71). There Wheatley presents a (seeming?) claim that acquiring the Christian religion made “Being Brought” worthwhile. But we should parse texts like this one very carefully, with awareness that she was crafting her lyrics for white readers of her day. In 1770, for instance, a poem she composed in response to the death of a popular preacher, Reverend George Whitefield, was published repeatedly, in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, and subsequently in London, to much acclaim from white readers.

“An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that celebrated Divine. . . . George Whitefield.” Library Company of Philadelphia

“A Poem: by Phillis, a Negro Girl, in Boston.” New York Public Library

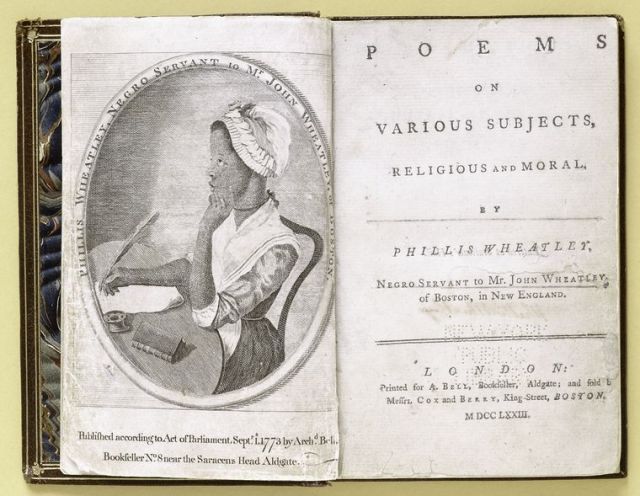

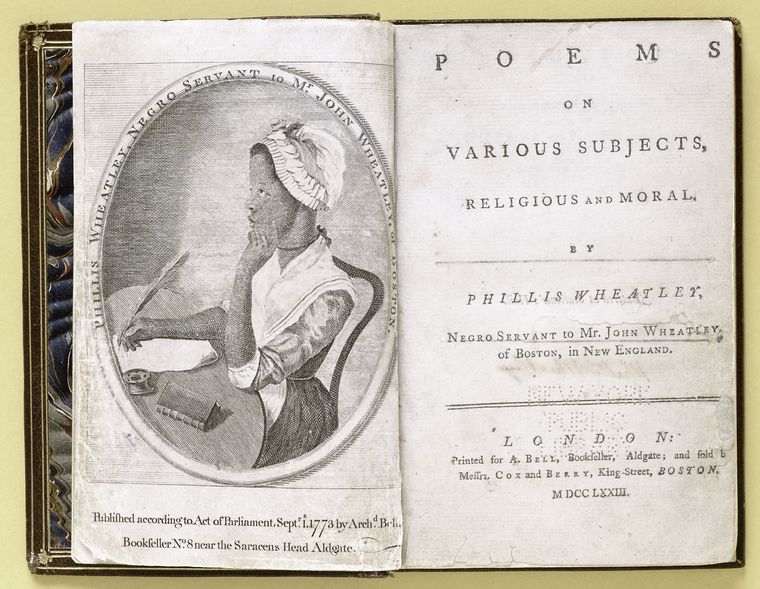

By 1773, although initially stymied in their hometown (at least in part due to some doubts about the ability of a young Black girl to create such texts), the Wheatleys successfully secured publication in London for Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, the first book of poems in African American literature.

Phillis Wheatley continued to draw enthusiastic readers from her white target audience. Joanna Brooks has assembled compelling evidence of a white women’s network supporting Wheatley’s poetry-writing as they “circulated her manuscripts, bought and sold her books, organized, hosted, promoted, and attended her domestic poetry performances, and commissioned from her original poems on subjects close to heart” (“Our Phillis,” 8). In 1776, George Washington wrote back effusively in response to a poem she produced in his honor during the Revolutionary War. As another sign that many white influencers (to use terminology of today) continued to admire her poetry well into the nineteenth century, we can point to Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of the blockbuster Uncle Tom’s Cabin): Stowe, in her second (less famous, but more radical) anti-slavery novel, Dred, imagined one of her main white women characters sponsoring “a second Phillis Wheatl[e]y” (Vol 2, Ch VI, “The Troubadour”).

In a more recent nod to that context of white readers dominating publications based in the experiences of enslaved peoples, Toni Morrison observed that Stowe didn’t write Uncle Tom’s Cabin for Uncle Tom—i.e., for Blacks, who knew the horrors of slavery only too well. Morrison could have said something similar about Wheatley. This girl genius author wasn’t producing texts for other Africans carried across what Paul Gilroy has dubbed the Black Atlantic. Scholarship by Elizabeth McHenry, Lois Brown, and others has demonstrated that there was in fact a substantial (and ever-growing) Black readership across the early decades of US history. But Wheatley’s initial access to publication came through white channels of social power. Part of her brilliance lay in her rhetorical sophistication, therefore—in writing on topics those arbiters would welcome (like elegies for bereaved families who had lost white children, like her salute to the Earl of Dartmouth when he was arriving in New England to serve as colonial administrator for the British). This history of her white audiences is important to acknowledge in our reading of Wheatley today. And understanding her writing also requires building knowledge, as Gates has pointed out, about why some Black twentieth- and twenty-first-century readers could see her as a sell-out.

Reading (and Not Reading) Wheatley in School Curricula

For a white educator like me, teaching Wheatley should emphasize ways that social power differentials—including race but also gender, class, geographic location, and varying spiritual practices—shaped her authorship. Seeing Wheatley’s texts through that kind of intersectional lens extends the purview for analyzing an individual poem (or her major Poems collection as a whole) into questions about systems of culture-building, as well as system-level constrains operating across time. One part of that work would also entail alerting students to subsequent generations of white cultural arbiters’ marginalizing (even erasing) Wheatley from the American literary canon. As a high school student growing up in North Carolina, I never encountered Wheatley—or Charles Chesnutt, or Harriet Jacobs, for that matter, other Black writers whose ties to my home state should have led to their inclusion in courses of study. When I began teaching American literature in Georgia and, subsequently, in Michigan in the late 1970s and 1980s, Wheatley did not appear in the school anthologies I was assigned to use.

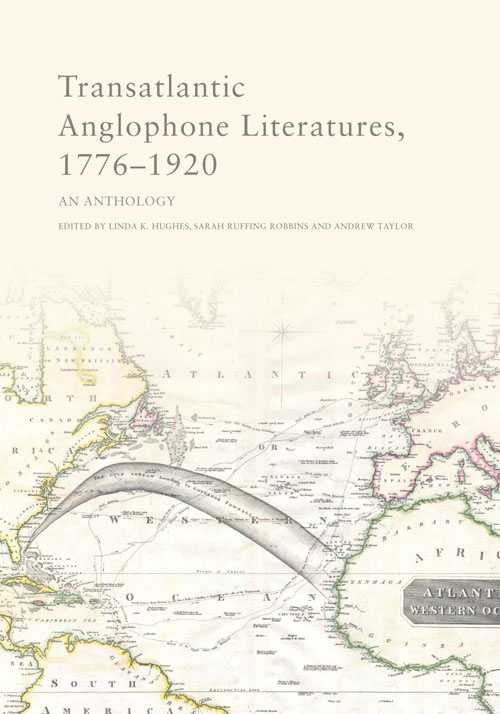

Not until 1990, when I returned to graduate school at the University of Michigan, did Wheatley appear prominently in a syllabus I studied, in Julie Ellison’s transatlantic seminar during my initial semester as a doctoral student. The first author we read, Wheatley arrived on my personal reading and teaching radar at last, in the form of a heavy spiral-bound course pack containing Xerox copies of the 1773 Poems. Under Ellison’s insightful guidance, we pored over Wheatley’s poetry in a comparative context alongside texts from both sides of the Atlantic in a long nineteenth century. In my own teaching about Wheatley since then, I’ve drawn, as most educators do, on having encountered her as a student: we teach with greatest confidence what we’re taught. But I’ve also expanded and adapted my studies of Wheatley into new contexts, such as a theme-based class on global diasporas. And Wheatley appears three times, along with headnotes to support students’ reading others’ teaching, in an anthology of transatlantic literature I’ve co-edited with Andrew Taylor, Linda Hughes, Heidi Hakimi-Hood, and Adam Nemmers. Including Wheatley there certainly didn’t need to be debated. After all, on multiple scholarly fronts besides transatlanticism (women writers, African American literature, history of the book, American literary history, children/youth studies, and more), she has commanded more and more attention since my high school days as student and, later, as teacher.

Another “Arrival”: Expanded Audiences for Wheatley

There’s now much evidence of a burgeoning interest in Wheatley besides in scholarly research and the classroom. One indicator lies in a book of contemporary poems honoring her, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ The Age of Phillis, which uses new poetry to creatively envision a richly complex life for its subject well beyond that bound up in her writings for white readers. (See Jeffers’ engaging story about preparing the poetic portrait of Wheatley here, where you can also read some of the poetry.) Another marker resides in the expanding number of children’s and YA literature biographies like Bunmi Oyinsan’s Phillis Wheatley: The Girl Who Wrote Her Way to Freedom, Kathryn Lasky’s A Voice of Her Own, and Ann Rinaldi’s Hang a Thousand Trees with Ribbons. When studying the excellent 2011 scholarly biography by Vincent Carretta, I noted this striking data point from his preface about how widespread Wheatley’s presence has become in a social media era: “Googling ‘Phillis Wheatley’ turns up over 33,000 items” (Preface). So I tried that step myself while drafting this blogpost and got over 800,000 hits: notable, exponential growth in just 10 years.

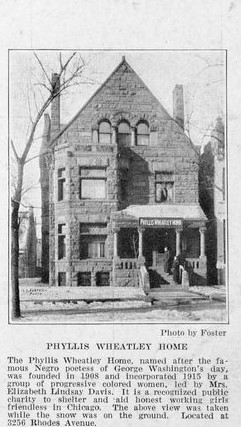

As early as 1925, if she wasn’t yet appearing regularly in literature curricula, one publication on famous houses in Chicago was offering up a photo of a social services center carrying her name. Since then, many other public sites all over the US (including schools) have been named for her. These days, we can also point to numerous historic markers like one at the corner of two streets in Boston where the slave ship Phillis docked in 1761. Fanning at least as far to the western US as a plaque on a Colorado YMCA named for Wheatley and back across the Atlantic to a disc-shaped metal engraving unveiled in London for her in 2019, such material records affirm that she has truly “arrived” to a kind of cultural visibility suggesting retrospective celebrity.

Wheatley In Canonical Curriculum

She’s also more firmly situated in the high school canon of American literature than she was before, during my own time in secondary classrooms. My admittedly un-exhaustive check among major 11th grade textbooks and adoption lists for large public-school systems and state curricular guidelines indicates that Wheatley is now a regular item in those American literature canons. That’s of course welcome news. Yet, I can give anecdotal evidence that she’s still not well known by the students I encounter in the range of courses at TCU, where I teach about Wheatley. My students typically say they can’t recall studying her before.

One reason may be that several of the major secondary school anthologies offer up a limited sampling of Wheatley’s writings in contexts that do not encourage analysis drawing on concepts like the Black Atlantic slave trade, constraints on African-American authorship in her time, or connections between Wheatley’s writings and the broader history of Black literary production in the Americas and beyond. I offer this inference based on a review of the three major American literature anthologies approved by the State of Texas Adoption Bulletin. (I chose this focus because a majority of TCU’s students still come from Texas but also because of the clout our highly populated state carries in the textbook marketplace). McDougal Littell (2008) incorporates only Wheatley’s “Letter to Rev. Samson Occum,” which it pairs with a letter from Abigail Adams to her husband John (254-58). (A CD companion to this textbook offers up a reading of this Wheatley letter that I found joltingly performed by a deep male voice.) The Mirrors and Windows anthology (2011-12), another Texas-approved textbook, includes two poems, “On Being Brought from Africa to America” and “To S..M., a Young African Painter, On Seeing His Works,” but labels them “Independent Reading,” suggesting an optional curricular status. In both of these Texas-adopted textbooks, sections where Wheatley is situated hold many more entries for familiar white writers than for voices recovered by scholars who have been promoting previously excluded writers, the sole exception generally being Equiano. Thus, teachers with limited exposure to African-American literature and/or women writers of color during their university training could easily skip over Wheatley entirely or afford her only cursory treatment, especially given these textbooks’ providing limited examples of other authors from within literary heritages beyond the most traditional. One noteworthy exception to the tendencies in the two anthologies above is the [year] edition of Pearson/Prentice Hall, another vendor on the Texas approved list. This anthology provides eight texts by Wheatley; besides the “On Being Brought,” the “To S.M.,” and the “Letter to Samson Occum” referenced above, this anthology features the elegy to Rev. Whitefield, “To Maecenas,” the poems to Washington and to the Earl of Dartmouth, and “To the University of Cambridge in New England.” This textbook brings the added benefit of being able to study Wheatley in conversation with a greater number of other writers of color (including Samson Occom and John Marrant, as well as several Latinx and Native American authors).

Another, newer exception to the rather limited approach in McDougal/Littell and Mirrors/Windows is Macmillan Learning’s American Literature and Rhetoric new textbook (2021 first edition), which is not (yet?) listed on my current home state’s approved list. Macmillan’s chapters 1-5 focus on writing in response to a range of texts, not all of them strictly “literary.” Chapter 6-10 continue to incorporate writing and rhetorical analysis activities but also present a chronological set of literary texts, so that this anthology (true to its title) seeks to address both writing and literature-reading aspects of the curriculum. In light of this expanded focus beyond more traditional literature anthologies for 11th graders, Macmillan’s choice to include three entries by Wheatley is especially noteworthy. Two of these (“On Being Brought” and “To S.M. a Young African Painter”) are also in the Mirrors/Windows anthology, as noted above, but Macmillan adds both “To His Excellency General Washington” and a text by June Jordan labeled as a “Talk Back” to Wheatley: “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America: Or Something like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley” (available from the Harvard Radcliffe Institute as an oral reading by Jordan here). While hoping to have more students in the future who have studied American literature with support from a textbook like this one or Pearson/Prentice, I recognize that the slowness of state-level and district-level adoption processes could mean it will be years before many students have had the benefit of such forward-looking materials.

In any case, whatever their textbooks in secondary settings, my university students may or may not have had a chance to work with teachers well versed in recent scholarship on a figure like Wheatley. Given the multi-faceted dimensions of their responsibilities at work and home, many secondary educators may be unable to update their American literature content knowledge for subfields like African American studies in pathways such as a state-level or NEH institute. I was one such teacher, prior to my doctoral work at Michigan. With small children at home, I struggled to find time for any reading beyond that provided in the basic curriculum materials I was given. I kept encountering signs that I was not up-to-date in my content knowledge, and I was eager to spotlight more texts reflecting the increasing student diversity in classrooms. But my access to advanced learning was constrained until I left my paying job to enroll in doctoral work.

At Michigan, I made the study of both American literature’s curricular history and its emerging developments as a field of study my priority. In the years since I had that special chance to renew my learning about American literature, therefore, I’ve tried to work collaboratively with other educators, across levels, to enhance our content knowledge and teaching approaches together—especially for writers like Wheatley, who were not a part of my own early studies of American literature. With that in mind, I’ll close by offering some examples of approaches I’m now using to introduce students to Wheatley. These strategies have parallels in my teaching of other authors formerly on the margins of curriculum. All of them are also readily available for out-of-school learners eager to engage with authors they may not have studied in school or university.

Ideas for Further Exploration of Wheatley

First, the major primary text, her Poems. When I was teaching high school, nineteenth-century literature had not yet become available digitally. Both Haithi Trust and Internet Archive have complete online editions of the 1773 book for which Wheatley is best known today. This access means we are not limited by print anthologies’ choices.

Second, though some scholars (such as Joanna Brooks) have pointed to holes in Gates’s striking portrait of Wheatley, his watershed 2002 Jefferson lecture (“Mister Jefferson and The Trials of Phillis Wheatley”) and its follow-up in The New Yorker (“Phillis Wheatley on Trial”) are easily retrievable online and intriguing for students to analyze on multiple levels.

More recently, students in my own classes have found one of The 1619 Project’s creative writing texts, Eve L. Ewing’s “1773,” a moving testament to Wheatley and thus a revealing window into her life and writing. Working in a conservative setting myself, I’m aware of the range of responses The 1619 Project has elicited. Whatever questions are being raised about the “version” of history being presented in this generative (if controversial) project, literature/language arts teachers can surely still draw on the parts of its content that are clearly designated as creative writing, including Ewing’s imaginative revisiting of Wheatley’s legacy.

For another current connection, in the coming academic year, I plan to pair several of Wheatley’s poems and some of the scholarship about her with the first-ever National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman’s performance at President Biden’s inauguration. Besides considering ways this particular text both echoes and resists traditions of white sponsorship of a Black voice, we can study some of the stories about Gorman, set in dialogue with media of Wheatley’s era in their representations of a Black youth as artist.

In that context, besides this essay’s words, the images within it offer material for interpretation.

These work could include considering comparisons with visual depictions of other young Black celebrity figures in our own time, whether Amanda Gorman, Simone Biles, or Black women writers with more control over their visual rhetoric than Wheatley could claim in her day (thinking here of Ebony Flowers’ Hot Comb and CaShawn Thompson’s Black Girl Magic project). Additional resources for such study come from Black women scholar-teachers addressing related questions about Black girl characters in culturally complex texts (such as the work by Ebony Thomas’s The Dark Fantastic and many writings by my TCU colleague Carmen Kynard).

I obviously don’t have the experience-based knowledge that these amazing current scholar-writers bring to their work, just as my own ability to tap into Phillis Wheatley’s life and authorship faces limitations grounded in my white racial identity. What I hope to do—what I will continue to try, from a standpoint of cultural humility and with a wish to keep learning—is to ensure that Phillis Wheatley not only arrives in my students’ and other readers’ literary landscapes, but that she stays, connects, and resonates.

References and Additional Resources

Brooks, Joanna. “Our Phillis, Ourselves.” American Literature 82.1 (2010): 1-28.

Carretta Vincent. Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage. 2011.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. The Trials of Phillis Wheatley. 2003.

Image Citations

“An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that celebrated Divine. . . . George Whitefield.” Courtesy Library Company of Philadelphia. Accessed July 27, 2001. https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A37980?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=5cebb7694e3328676a51&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=1

“A Poem: by Phillis, a Negro Girl, in Boston.” Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “A Poem” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bfc8d8be-ccc3-94e2-e040-e00a18065961.

“Phillis Wheatley.” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Phillis Wheatley” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7eb749fd-962d-11f1-e040-e00a1806548b.

“Phillis Wheatley Home.” [Chicago, 1925]. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “The Metropolitan Community Club House; Old Folks Home; Phyllis Wheatley Home.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47de-5185-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

“Title page and frontispiece.” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Title page and frontispiece” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 27, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-19df-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

“Wheatley, Phillis, 1753-1784.” Courtesy Library Company of Philadelphia. Accessed July 27, 2021.https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A35812?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=5cebb7694e3328676a51&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=2

Pingback: Celebrating A Writer’s Life in a Participatory Humanities Project: – Sarah Ruffing Robbins