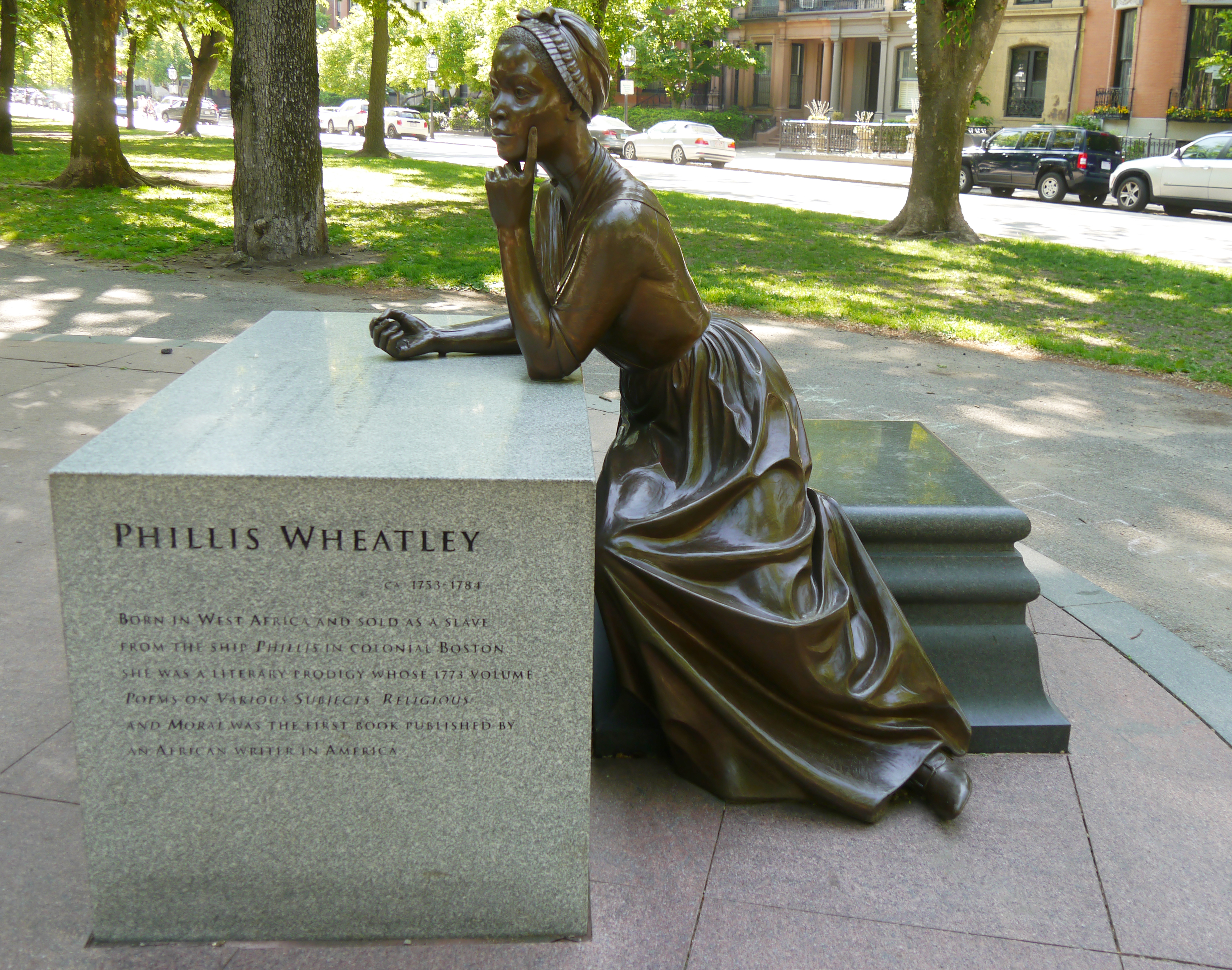

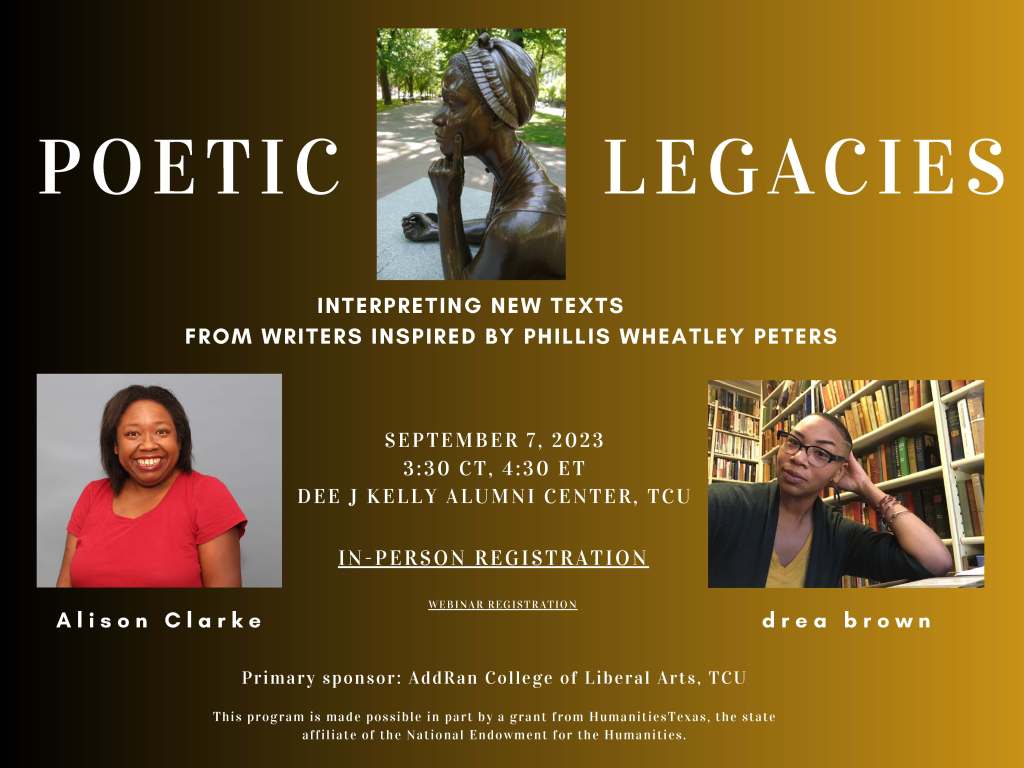

As one of the codirectors of a year-long initiative honoring the life and work of Phillis Wheatley Peters, I’m pausing this week to reflect on our collaborative project’s progress. Reflection, after all, is a habit of mind and an action that representations of Wheatley Peters herself tend to associate with her writing and her life, as seen in the Boston Women’s Memorial‘s portrayal of her.

Photo by Sarah Ruffing Robbins

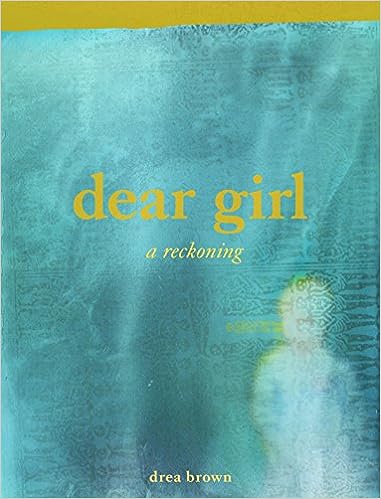

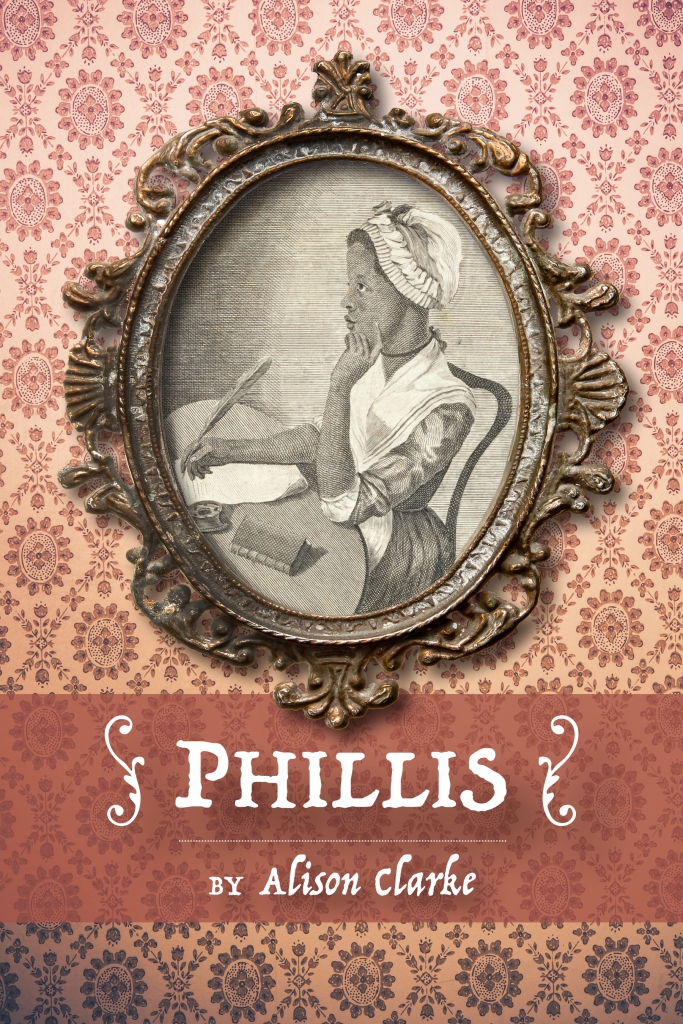

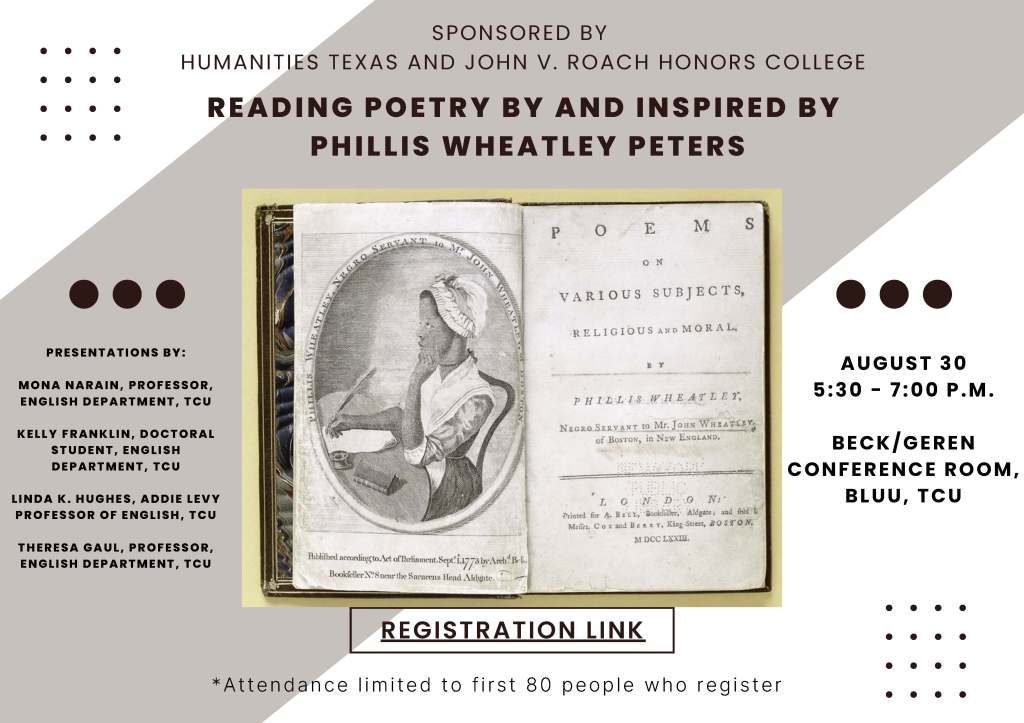

This is an apt time for reflection. For one thing, as the e-newsletter “This Week in Literary History” has observed, Wheatley’s book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published at the beginning of September in 1773. So we have reached a major anniversary week within our anniversary year. For another, our project team has now completed a generative set of initial activities: one academic semester (spring 2023) and a summertime smaller cluster of events tied to this anniversary year. We’re now launching our fall programming. As I’m composing this website posting, at the end of August, I’m looking ahead to an August 30 roundtable of TCU faculty members who will share poems from Wheatley’s important 1773 book and set them in dialogue with recent texts inspired by her story and her authorship—specifically by drea brown (in dear girl: a reckoning) and Alison Clarke (in Phillis).

Alison and drea are both coming to Fort Worth September 6 and 7 for several highlight activities in our programming. On the 6th, they’ll spend time at a local high school, immersing in poems by Wheatley along with students. In a second session that same day, they will collaborate with teachers to envision interdisciplinary approaches for teaching Wheatley Peters and her legacies. On the 7th, they’ll be the prime presenters in a roundtable, a hybrid event combining an in-person audience on campus with webinar attendees, including moderator Aruni Kashyap from our sister institution in the PWP project, the University of Georgia at Athens.

On both days when Alison and drea visit, as I’ve done since our project began back in January (with planning, of course, starting months earlier), I’ll have an unparalleled opportunity to learn along with other participants about Wheatley Peters and her ongoing impact through cultural memory.

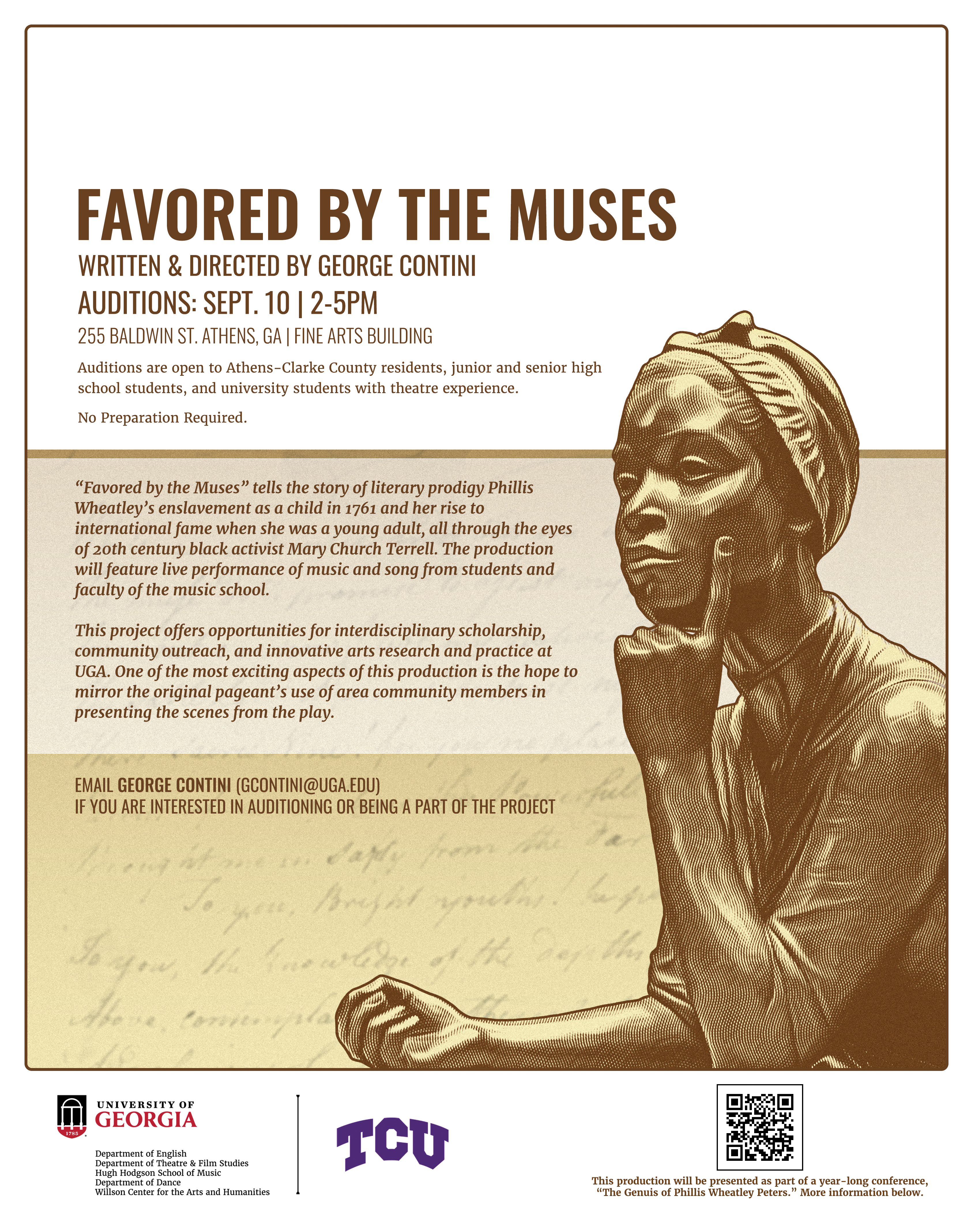

Still to come on our calendar are a student writing contest, an October family literacy event spotlighting children’s and YA texts focused on Wheatley, and a November 15 roundtable of scholars assessing current trends in research on PWP and its links to social issues of our own time. Additionally in November, UGA will host the world premiere of a play honoring both PWP herself and a previous pageant on Wheatley created by Mary Church Terrell in the early twentieth century.

UGA Theatre Tryout Announcement; Mary Church Terrell from NYPL Digital Collections

When I scroll back through the array of activities embedded in our project—both those already held and those yet to come—I’m struck by the rich variety of ways we’ve found for engaging diverse public audiences in Wheatley Peters’s many legacies. We’ve had scholarly presentations, to be sure, but also conversations with teachers, new storytelling in a range of genres, readings of PWP-related texts aimed at many different audiences, and connections with some of the exciting artistic performances still being inspired today by PWP. I’ll treasure, for instance, the opportunity the project presented for me to attend the world premiere of Written by Phillis at Quintessence Theatre in Philadelphia.

Photos by Linda Johnson, Courtesy of Quintessence Theatre

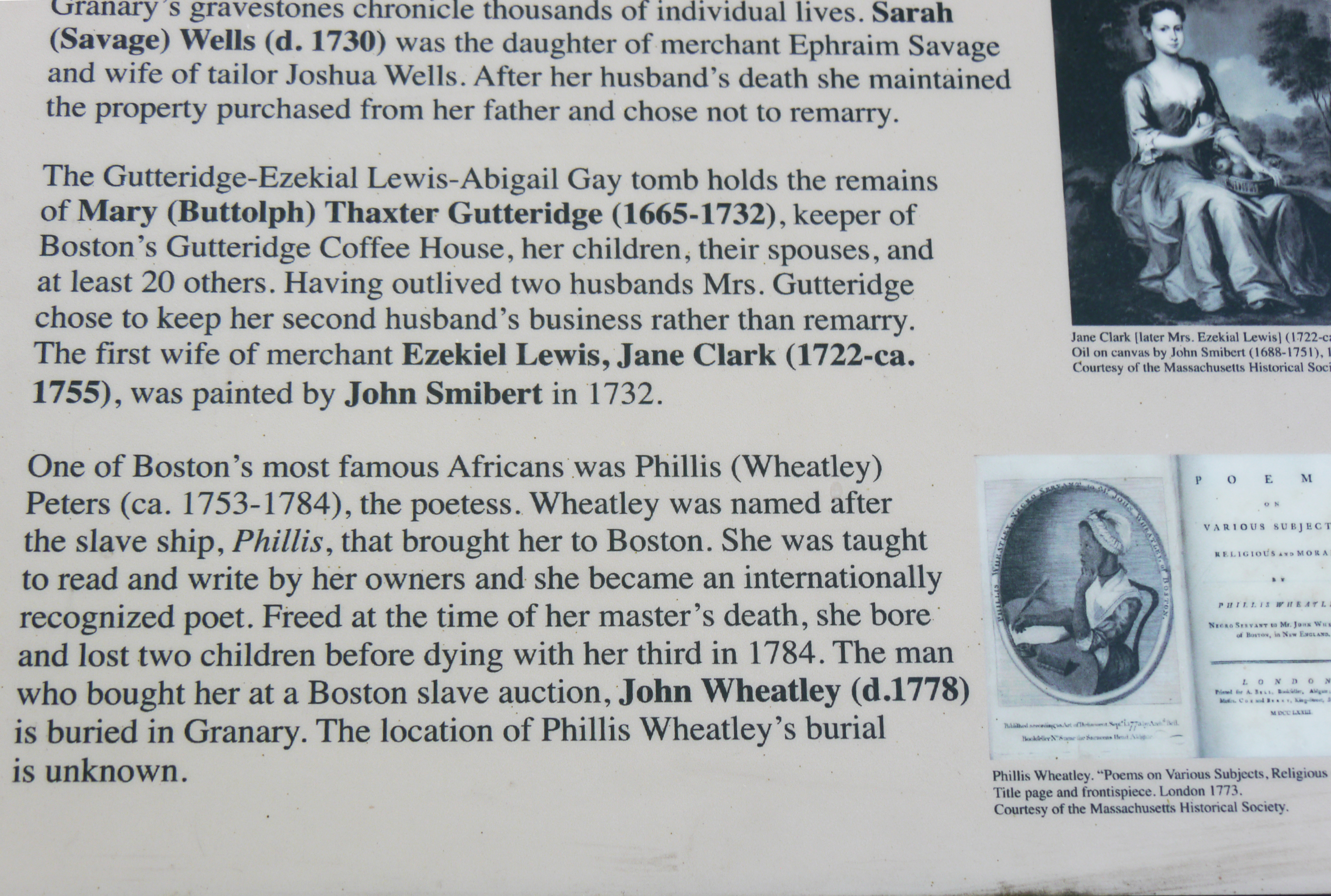

Also during summer 2023, I took time to create my own walking tour of places in Boston related to Wheatley Peters’ personal life there. Camera in hand, I recorded both increasing efforts to weave her life into the fabric of the city’s past and gaps in that visual narrative–some due to metropolitan reconfigurations of space (new buildings and streets, over time) but others due to hierarchies in social status associated with distinctions between being free members of the Wheatley family (John, Susanna, and their children) versus being enslaved, however distinct Phillis’s opportunities to study and write.

Photos by Sarah Ruffing Robbins

Another energizing Boston tie for my own project participation came when a reporter from the Boston Globe arranged a Zoom small-group interview with project codirectors Barbara McCaskill, Mona Narain, and me. My TCU colleague Dr. Narain compellingly reminded us during that conversation that, however much some might associate “Wheatley” today with historical moments like the American Revolution, however much a specific place like Boston might seek to claim her, Phillis Wheatley Peters was a transnational phenomenon. Long before terms like “global cosmopolitanism” circulated as widely as today, she embodied and enacted such a role. In her vast store of transtemporal and transcultural learning, in her experiences moving from being a British colonial subject to an inhabitant (but not a citizen) of a nation self-conscious in its complex newness, she demands multi-faceted interpretive approaches.

One tool supporting such efforts by our project team is the World Wide Web.

Throughout our initiative, I’ve had the special pleasure of supporting TCU students’ many contributions to our website. For example, I listened and learned from Colleen Wyrick while she collaborated with playwright-scholar Ade Solanke to reflect on the dramatist’s ongoing writing process for a play focused on Phillis Wheatley’s time in London. Colleen’s three-part podcast, “PWP On Stage,” joined a growing collection of mixed-media contributions to our project website. When we began to build that website, I anticipated only a modest set of informative pages providing registration links to our various events. But student enthusiasm for new-media-enhanced storytelling about Wheatley Peters led to numerous ambitious and generative contributions, such as Claire Litchfield’s interview with researcher Wendy Roberts. And our initial website designer—then-undergraduate (now grad student) Adrienne Stallings quickly recognized the capabilities a website offered for building a project archive. Her leadership ensured that our efforts could visibly and continually contribute to the larger, ever-growing archive of inquiry into PWP’s life, writings, and legacies. We recorded and uploaded videos from a number of our past events, for instance. We shared digital posters that originally served as promotion texts and registration paths but became an important preliminary record of our work. We set up connections to partnership efforts like one creating a university LibGuide of resources, with parallel versions at both TCU and UGA.

Before long, we started hearing from others beyond our original collaborative partnership of TCU and UGA—colleagues encouraging us to spotlight their parallel (“Sister”) projects, something we were honored to do, as well as volunteers offering new contributions to the work.

These days, we often hear the term “public-facing humanities” used to distinguish endeavors like this one from more traditional academic scholarship like journal articles and books for specialists. Public-facing does convey a commitment to reaching beyond the (so-called) “siloed” walls of the university. But our project is aiming for more than addressing broader audiences: we seek to engaging them in shared inquiry. For us, the best public humanities work is communally shaped and generatively participatory. Phillis Wheatley Peters is proving to be an ideal focal point for putting such a vision in action.

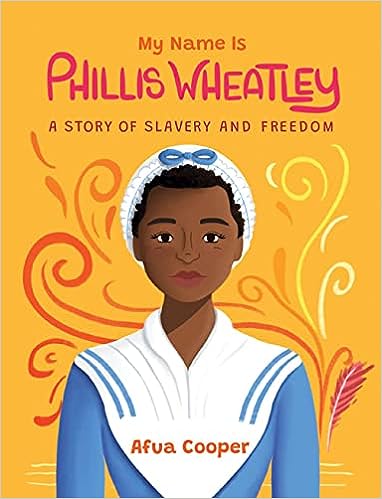

This week, for example, I re-read My Name is Phillis Wheatley, by Afua Cooper, with a seminar of first-year students. Cooper’s biography uses a first-person approach to draw readers into PWP’s life history, including via scenes from her life in Africa before her enslavement. After we discussed the text, I asked my students to freewrite thoughts on how they might attract someone else to the book and to engagement with PWP more broadly. Some wrote as if persuading a roommate; some imagined taking their book home to share with parents or hometown friends over fall break.

They identified notable features of the text—and Wheatley Peters’ life and writing—they viewed as valuable. Let me roughly paraphrase from my in-the-moment notes on their responses:

Wheatley’s being our age when she published her book inspires me to think my writing could matter.

Wheatley’s life reminds us we benefit from studying history—especially history that doesn’t always get enough attention in school today.

Seeing how Cooper used her academic training to tell a compelling story helps me see how research and imaginative writing can come together.

Reading about PWP’s life reminded me that literature builds empathy. The first-person approach made me identify closely with Wheatley Peters and her feelings about being captured, enslaved, and trying to adapt in a different culture: something I couldn’t do in a dry third-person general history.

Listening to these responses, I heard echoes of brief anecdotes from one of our project’s earliest webinars, when codirector Barbara McCaskill asked a January panel of scholars to share reflections on how they first came to know about Wheatley Peters, and what she means to them today. Everyone’s story underscored the importance that a figure like PWP can hold in our lives across time, in a wide array of circumstances, and how we can continue to expand our knowledge and appreciation of her meaning by sharing our inquiry with others.

Connecting my memory of that launch session for our project with my current excitement about introducing new audiences to PWP in classrooms and beyond, I know “The Genius of Phillis Wheatley Peters” is a project that won’t actually have an endpoint. Well beyond the closing days of 2023, more learning and more collaborations lie ahead.