One link-up certainly invited by this text is to revisit Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Indeed, I’m currently re-reading Twain’s novel after recently completing Everett’s. And I may have some more detailed thoughts to share in that regard soon.

Already, though, just through a remembering of the nineteenth-century text while working my way through James, a few general points of comparison and contrast stand out. I’ll be eager to hear from others in my book club group (meeting in late June) what juxtapositions they have noted.

On my own reading, I’ll dispense first with what I found to be the clearest dimensions of consistency in Everett’s retelling. One is the characterization of Huck, who, it appears to me, speaks, acts, and interprets his lived experiences in this narrative in ways that generally echo the earlier book. Huck is smart. He has suffered some setbacks in his life—including being abused by his white father. Yet, he maintains a relatively optimistic attitude. He is also innocent, in the relatively positive sense of being a child whose racist attitudes and commentaries can, to an extent, be attributed to his youth—as in he is “innocent” enough to be (partially) excused for the limitations in his perspective. He is also “innocent” in the less appealing sense of being technically “innocent” of law-breaking, again due to his age, even if he “knows better” than to steal things (which he and Jim/James both do, individually and together), or tell lies, or run off with an enslaved person—all of which both authors likely assume readers can excuse Huck for doing.

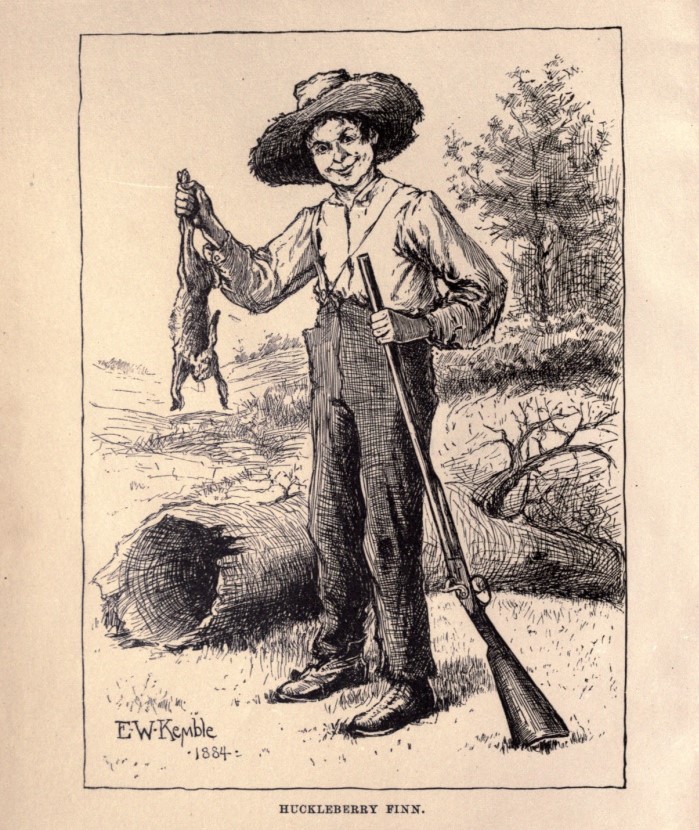

Images of Huck from the frontispiece and the closing pages of Twain’s first US edition.

At the close of the new Everett-envisioned revision of this tale, Huck is also innocent of carrying out serious, permanently destructive violence (spoiler alert), and in some ways that innocence is made possible by Jim’s/James’s loving care. Interestingly, scenes near the end of Twain’s novel that depict Huck back in the thrall of his “comrade” Tom Sawyer (to invoke that book’s subtitle) and thus caught up in an ethically inexcusable abuse of Jim (making a “game” of hiding him in shackles and thus re-enslaving him unnecessarily) do not appear in Everett’s account. So it might even be said that Everett’s Huck is, at least at that stage in the narrative’s progression in James‘s last episodes, a better person than in the 1880s’ text. In fact, Huck takes on several potentially dangerous tasks in an attempt to aid a potential escape for the James of the newer tale.

Overall, I suspect that with a deeper dive back into Twain’s narrative, I will find more nuances to explore around the similarities and differences in the two Hucks. For now, a point already worth emphasizing and related to the basic differences in the two books resides in this seemingly obvious point: Everett’s account, from the title forward, places JAMES at the forefront. Huck rightly becomes a secondary character, in rhetorical service of Everett’s protagonist.

A second point of evident comparison between the two novels has to do with features connected in similar ways to their shared setting. Both narratives take place along (on and in communities near) the Mississippi prior to the Civil War. (One distinction worth noting: Twain’s title page says his book is set in “The Mississippi Valley” at a “Time: Forty to Fifty Years Ago,” so given the 1884/5 publication date [the earlier in Britain], the events are well before the outbreak of the Civil War. Everett, on the other hand, has his characters hear news of the outbreak of the war, and he has Huck imagine enlisting.) Minor characters who appear in both texts act consistently with that shared antebellum time and region. Several characters invented by Twain—such as the Widow Douglas and Judge Thatcher, Tom Sawyer, the Duke and the King—reappear in James. But Everett eliminates or marginalizes plot elements from the original text (such as specific episodes of the feud between the Grangerfords and the Shepherdsons). As I first began encountering these distinctions, I associated them (I’m a professor, after all) with the shift in point of view. James can’t report on events experienced only by Huck, when the two are separated from each other. But the further Everett takes us into his own narrative, the more he delivers brand new plot turns tied to James himself and his deepening characterization. Many of these give this book’s title character a much-enhanced agency over his forebear. Some increasingly highlight both the horrors of slavery and an argument that resistance by any means can be adopted as both necessary and righteous.

This last point brings me to a second intertextual reading path I found myself taking in the closing chapters—to Kyle Baker’s powerful 2008 graphic novel, Nat Turner. I stopped teaching The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn long ago. (In fact, I think I actually last brought it into my university classroom about two decades ago, and from a stance critical questioning.) I have used several illustrations by the first edition’s artist, Edward W. Kemble, in classroom analyses of his representations as visual rhetoric invoking racist ideologies. But I haven’t asked students to read Twain’s novel in years. I have, in contrast, taught Baker’s intense depiction of Turner’s life and rebellion and death in several different contexts. I tend to preface that study with a freewrite asking students to respond to this question: When, if ever, is violence justified?

Almost every student will make a case for violence as justified if one’s own life or one’s family is threatened. We discuss those responses and the rationales behind them before they begin reading Nat Turner. Baker himself presents a related ethical scenario set-up in the opening pages of his book, where he vividly shows a raid on an African village. Enslavers capture and kill. Horrific cenes from a Middle Passage ship follow. These drawings, students frequently suggest, prepare readers at least to accept if not affirm Turner’s violence. Percival Everett makes similar moves in episodes he adds to his revisiting of antebellum America. Then, besides having his characters see (if at a distance) the Civil War beginning, he repositions Jim from relatively passive victim of enslavement to his own James as an active, resistant leader, one who embraces violence as necessary.

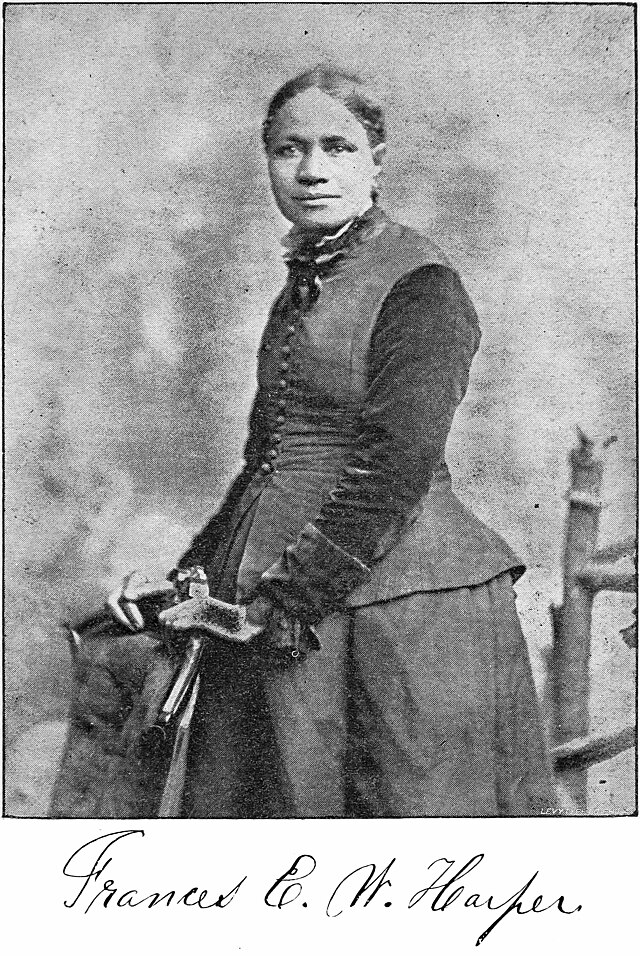

Significantly, though, even as this novel makes that striking shift, thereby echoing not just Baker’s graphic novel but also Quentin Tarantino’s over-the-top Django Unchained (2012), this Huckleberry Finn counter-story also invokes familiar celebrations of less overt and violent means to agency: assertions of literacy and its power familiar from African American literary history. Frederick Douglass’s and Frances E. W. Harper’s accounts (such as in Douglass’s autobiography and Harper’s Chloe poem cycle) of stealing reading and writing as one way to claiming agency certainly come to mind when Everett has James use the Judge’s library on the sly, speak in a learned brand of English when whites are not listening (including as narrator), and, perhaps most memorably, treasure and repeatedly employ a notebook and pencil to write about his experiences and reflections.

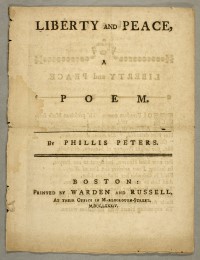

James’s pencil—while not an immediately destructive weapon—speaks to the eventual agency of Black writing across time, of Black literature as justice-oriented storytelling. Because I’ve been working so much on Phillis Wheatley Peters over the past couple of years, and teaching not only her biography but also her writings and writings about her, I found myself thinking about James’s tightly-held pencil as a counterpoint to the quill pen so often discussed in relation to the frontispiece of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. As others have duly noted, that author (then designated only as “Phillis Wheatley” via a naming assigned by her enslaving Wheatley family) is marked as held by that family in verbiage that encircles her portrait to name her as “servant to Mr. John Wheatley.” Thus, the quill she holds—though it conveys a sign of her literacy—is also not fully her own. This brand of literacy, however admirable in its brilliant appropriation of white poetic models, can’t help but also be constrained. If, as Tara Bynum’s research has shown, young Wheatley wrote for herself and her friend Obour Tanner in their private letters, in her published poetry, she wrote mainly for white readers. Her pen, like her poems, was not fully her own. At least not in 1773, before being freed and choosing to become Phillis Peters.

Frontispiece, 1773 and title page for broadside published after PWP’s marriage, signed accordingly

In Everett’s novel, James’s pencil, stolen from a white man, provided to him by a Black “comrade” in real—not childishly pretending—adventurous revolt, comes at great price. That Black brother is killed, making retaining the pencil all the more necessary, as is acquiring paper to write upon. James claims his own name. He writes his own story, both on paper and in action. Ultimately, in other words, for Everett and his insistent retelling of an old story, this Black man will choose new routes, taking family and others along with him—hopefully his readers among them.

IMAGE CREDITS:

All images from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn come from Haithi Trust, which provides a copy of the 1885 US edition originally made available through Internet Archive. Here are links to those two online editions of the text, which is in public domain: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t3cz3334b&seq=11 and https://archive.org/details/HuckleberryFinn1885/mode/2up.

Book covers for Baker’s text were downloaded via Bing images using the “Public Domain” filter. For James, the cover comes from the publisher’s profile page for the novel, here.

Numerous photographs of Frederick Douglass, like the one included here, are available in Wikimedia Commons, and together they give a sense of the range of images circulating during this famous writer’s lifetime and beyond. To see examples, go here. Similarly, the photo of Harper comes from this collection in Widimedia Commons.

Many copies of the frontispiece for Wheatley’s 1773 book of poems are available through sources such as Haithi Trust and Internet Archive. This image is likely the one most often associated with the poet.

The title page for her 1784 Liberty and Peace publication–one of a few texts released as a free-standing publication after the poet’s marriage to John Peters–comes from A Celebration of Women Writers website of the University of Pennsylvania, here.